Opposition to a 10 team World Cup has been the hot topic this month. Everyone is having their say, from the eloquent Ed Joyce to the potentially paradigm shifting Sachin Tendulkar. The arguments are well rehearsed by us grizzled champions of global development but they have now reached a broader audience and momentum is building fast, with a petition against the depressingly short-sighted reduction setting social media abuzz.

Opposition to a 10 team World Cup has been the hot topic this month. Everyone is having their say, from the eloquent Ed Joyce to the potentially paradigm shifting Sachin Tendulkar. The arguments are well rehearsed by us grizzled champions of global development but they have now reached a broader audience and momentum is building fast, with a petition against the depressingly short-sighted reduction setting social media abuzz.

That isn’t to say that everyone agrees. Gavaskar, a legend of the game who you would hope and expect to be a champion of its growth, insists that all world cup games must be competitive and that to ensure this the associates should be excluded. The results of the tournament so far have exposed that presumption as nonsense. Equally easy to debunk is the popular myth that inclusion of the associates makes the tournament bloated. That, as we all know, is to do with a format designed to have as many guaranteed ‘marketable’ fixtures as possible.

So why is cricket set to contract its World Cup when all other sports are using their flagship event as an opportunity to expand and grow the game? The answer, of course, is money. There was a revealing passage in Dave Richardson’s interview with TMS last year when he set out the core objectives of the ICC. Maximising revenue of its global events was front and central. Global development was conspicuous by its absence. The logic goes that a format with as many ‘marketable’ games as possible attracts the biggest bid, and therefore that the ICC’s hand is forced. Ireland knocking out Pakistan in 2007 was not, in commercial terms, acceptable. And the associates are set to pay the price for that heart-warming achievement.

No-one would argue that money isn’t an important factor for a sport desperately fending off football’s attempts at hegemony in the media marketplace. But maximising revenue for a single tournament is a very narrow perspective on brining money into the game. In the short term denying associates a place may lead to a bigger pay cheque, but in the longer term it will deprive cricket of emerging and potentially lucrative markets. How can reducing opportunities be a sport’s model for growth? It is plainly counter-intuitive. But the ICC is hampered by its arcane and archaic governance structure that forces it to put short term riches for its full members before the future health of the sport. We should not forget that the ICC commissioned a report into its governance and then promptly rejected all the proposals intended to make it into a modern, efficient governing body.

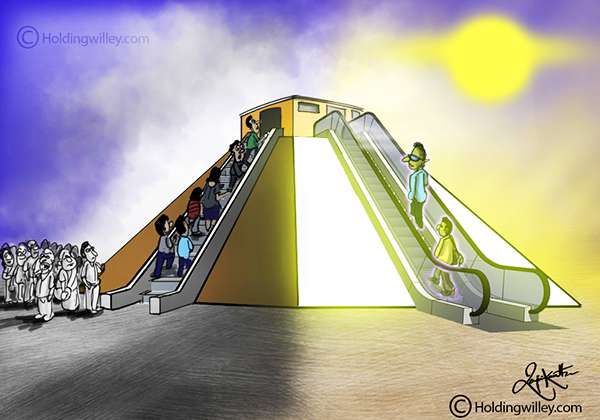

So what can the ICC do? If they insist on a minimum number of teams in a World Cup in order to give credence to its stated ambition for a ‘bigger, better global game’ then the full members will block it through fear of a smaller pie from which to take their fulsome slice. They try and persuade the full members to take a longer term view, but the individual boards are steered by self-interest into maximising revenue under their tenure. In organisational-political terms any concession would be perceived as weakness. Money determines the short term nature of decision-making in cricket. Those at the table benefit, those who will suffer are those denied a chair and scrabbling on the floor for the scraps.

“

The ICC is looking to decrease dependency of its associate and affiliate members on their grants. And it is true that many have not put enough effort or ingenuity into attracting other revenue streams and are guilty of resting on their laurels. However, there is a very simple solution that could have a transformational impact on the globalisation of cricket: the Olympics. The ICC is concerned that in becoming an Olympic Sport there will be a global event featuring cricket over which it does not have control and cannot make money from. In the very narrow sense of controlling media contracts they are right. However, Olympic status would see money flowing into the game from national sporting bodies, providing the means to grow cricket in emerging and new markets across the world. Once grown of course these countries would be lucrative markets. It is the key to cricket’s growth in China, a market the ICC is courting. But short termism makes cricket blind to these possibilities.

”

Traditionally development of the global game has been viewed as a philanthropic exercise. From the good of their hearts the ICC would support growth in the hinterland beyond and between its gilded citadels to fulfil its nominal role as governing body for a global sport. In fairness this philanthropy has left a mark in the work carried out by the regional development offices, High Performance Programme and the competitive structure created through the World Cricket League and Intercontinental Cup. But, patience with philanthropy grew thin. If the tangible benefit of all this good grace was for an associate to clip the wings of a full member then was it all worth it? And now the future is uncertain, with the role of regional offices up in the air and a 10 team World Cup completely undermining the development structures that have been created.

But why is philanthropy the watchword? Why is global development seen as selfless? As has been seen in the West Indies, cricket is not as impregnable in its full member fortresses as the ICC would like. India now has a star-studded football league quickly gathering momentum. Wouldn’t it be criminally complacent for cricket to define the curtilage of its influence around traditional centres that face many pressures now and in the future? It is hardly, in corporate parlance, a future-proofed policy. Contracting opportunities will of course lead to a withering on the vine of emerging and exciting cricketing nations. Supporting emerging cricket nations is not a philanthropic exercise, they have the potential to expand and extend cricket’s global popularity, marketability and revenue.

All of which brings us to cricket’s other ‘m’ word: Meritocracy. There is surely not a more popular term in ICC press releases than ‘meritocratic pathway’. The idea that a team can attain greater profile, opportunity, riches and ranking through merit is a wonderful one. But that isn’t what we have. Due to its governance flaws the ICC is obligated to protect its full members. And why would its full members want its fortunes dictated by merit when age old privileges serve them much better? Why would they vote for demotion or a reduction in revenue? In that context a meritocratic pathway is impossible. In effect it just means that teams like Afghanistan can qualify for a world cup and get an increase in their funding.

So, having exposed these rather depressing truths what can champions of the global game do? Well, there are several options. Some have come to the conclusion that the only option is to topple the status quo and build again from scratch through a truly meritocratic organisation. In this future there is no status protecting the privileged few and holding back the many.

The other option is what you might term piecemeal pragmatism. This is the approach followed by the ICC development team. Those who favour this approach understand that the structural constraints of the ICC mean that fair, meritocratic and forward looking proposals will be blocked by self-interest. So any reforms have to be gradual and not tread on full member toes. An example of this is the recent removal of the historic right of full members to qualify for World Cups and the World T20 automatically. Unfortunately this was not coupled with a commensurate extension of opportunities for associates. But, it does bring leading associates and weaker full members closer. A simple and non-controversial pragmatic reform that could and should have been implemented is the extension of ODI and T20I status. There is simply no logical reason why at least the best ten associates should have this status. Being deprived of status merely reduces their ability to raise profile, participation and revenue and thereby, ironically, increases their reliance on the ICC grant.

It is important to note that both camps share the same goal (and implicit in that is that the ICC, or many voices within it at least, is as passionate about global expansion as fans are) but have different views on how best to achieve practical outcomes. In the coming months and years these two groups will be watching developments closely, seeking evidence to support their point of view. Will the ICC take note of the opposition to the 10 team World Cup, instigate positive reforms and take the rhetoric of meritocracy to heart? Or will money and short-termism continue to hold sway? We shall see.

Tim Brooks is Head of Cricket for QTV Sports and can be found on Twitter at @cricketatlas.